Children's Minds in the Line of Fire COCAP Blog

Self-Harming Behaviours

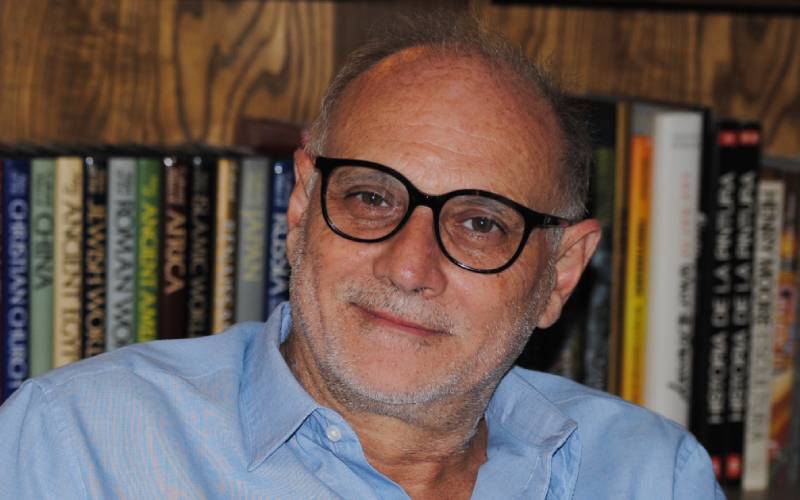

Humberto Lorenzo Persano MD; Ph.D

Training and Supervising Psychoanalyst - APA

Self-harm is a common clinical phenomenon in many adolescents and young adult patients. The presently observed increase in the incidence of self-harming behaviours may be related to features of our contemporary world and reveal a deep malaise among young people.

It is common today for adolescents to watch their peers hurting themselves on social media, and this has contributed to an increase in self-harming conduct in adolescence. This phenomenon al-lows them to identify with one another and to replicate these situations of violence in a masochistic choreography. Adolescents may be particularly vulnerable to social contagion, due to the intensity with which they seek a sense of identity and belonging.

In addition, there are a number of potential intrapsychic, familial and social dynamics associated with self-harm. Self-harm has been associated with personality and depressive disorders, psychosis, eating disorders, and substance abuse. The presence of self-harming behaviour is a predictive indicator of suicidal behaviour, especially in vulnerable populations. People with representational deficits, impulsive modes of psychic functioning, and difficulties with self esteem regulation are more likely to self-harm.

Self-harming episodes are more common in female adolescents than in males and may represent an attack on emerging female sexuality. There is also a correlation with dissociative symptoms. Patients treated for self-harm sometimes show little ability to remember how their self-harm occurred or what feelings they experienced during the episode. When patients can recall these experiences they often use phrases like; “I don’t know what happened to me, I couldn’t take it anymore and I cut myself, I reacted when I saw the blood …”

On the familial level, families in many places in the world are exposed to precarity and violence. This can lead to domestic aggression, which in turn can increase aggressive behaviour in children and adolescents, who often direct aggression against themselves. Domestic aggression is linked to childhood traumatic experiences, and the self of the infant may cathect with a greater amount of aggression than erotic libido. Also, the inability of both the family and society to establish an effective shield to protect the development of the child’s psyche, along with the increase in disturbed inter-personal relationships, disturbs the regulation of aggression. All these factors contribute to an increase in self-aggressive behaviours in families and in cultures more broadly.

Self-harm is a way of communicating, through action, psychic pain and self-vulnerability. Selfharm provides a means of ephemeral relief through psychic and somatic discharge. During self-harming behaviours, split off aspects of the self, unknown to the subject, emerge. Despite the masochistic features of these acts, they may be an opportunity to acknowledge unfathomable aspects of one’s own being.

Self-harming is associated with affective aggression which is triggered by emotions like anger, sadness, and emptiness. The role of archaic masochism is associated with this condition, and it is a form of identification with an aggressor. Some individuals who self-harm use masochism to deal, unsuccessfully, with different types of conflicts. In clinical practice, we have seen these manifestations especially in the face of conflicts unleashed by situations of real or imaginary abandonment. These patients tend to use immature and archaic defense mechanisms tied to patterns of action that they turn against themselves when faced with the emergence of unprocessed painful scenes. Masochism is thereby intertwined with phenomena of aggression, impulsiveness, and violence.

Self-harming is also associated with addictive phenomena. Addictive behaviours involve repetitive compulsion and an unconscious pursuit of reward. This addictive dimension is seen in people who hurt themselves repeatedly on their wrist and forearms, as well as through the repeated ingestion of drugs or threats of suicide. Although every expression of acting out is risky, the sense of reward from being cared for is intense, and thus these expressions tend to be repeated. They can also be related to the death drive. Through inflicting painful and punishing situations upon one’s own body, the subject can submit to the drive for non-existence.

The ethical dimension of the conflict is the source of an unbearable tension between the ego and the superego. In some cases, the perceived failure of not reaching an ideal is manifested as aggression impulsively directed against the self or against a part of the body, showing masochistic and narcissistic components. All these manifestations are associated with expressions like “I couldn’t take it anymore”, which denotes extreme psychic suffering and a need for a massive release of painful feelings.

In contemporary society, violence is not only physical but is also expressed through social discrimination. In today's culture, social discrimination takes on various forms, with cyberbullying acting as a potent amplifier. Instances of violent social discrimination can become catalysts for individuals engaging in self-harming behaviours.

Episodes of bullying among peers further exacerbate the issue. Adolescents and young people may resort to self-harming behaviours in an attempt to manifest their discontent with problematic social values. The experience of being marginalised is a social phenomenon, but it also impacts adolescents narcissistically. It can result in a sense of a damaged self. That is, the humiliation feelings generated by these social issues, become intertwined with this narcissistic offence, leading these adolescents down the path of self-harming masochistic situations.

Understanding these complex situations requires a theoretical framework that views self-harm as a primitive and archaic mode of expression. It is simultaneously a manifestation of social discontent, showcasing intensified forms of adolescent psychopathology.

Author: Humberto Persano, Md. PhD.

Author: Humberto Persano, Md. PhD. Psychiatrist and Doctorate in Mental Health (UBA). Psychoanalyst - Full Member and Training analyst and Specialist in Children and Adolescents - Argentine Psychoanalytic Association (APA) and the International Psychoanalytical Association (IPA). Full Professor in Mental Health and Psychiatry (UBA). Director of Institute of Clinical Psychiatry and Mental Health “Domingo Cabred” (UBA). Head of Department on ambulatory services at the Jose T. Borda Mental Health Hospital. Past General Director of Mental Health Services in Buenos Aires City. Member of the Health Committee (IPA). Reviewer - The International Journal of Psychoanalysis (IJPA), since 2009. Fellow Member College of International Journal of Psychoanalysis (IJPA), since 2016. International Fellow of the American Psychiatric Association. Research Fellow Member – Joint International Psychoanalytical Association (IPA) & University College London (UCL), 7° RTP, 2001. IPA College of Research Fellows.

Back to Children's Minds in the Line of Fire Blog

Back to Children's Minds in the Line of Fire Blog