Img: Daniel6D/Pixabay

Reflections on Mass Shootings

Psychoanalysts Leda Herrmann, Luiz Moreno Guimarães Reino, and Fernanda Sofio reflect on the psychology of mass shooters.

well: pharmacies don’t offer, not yet,

ways to jump out of a jet.

João Cabral de Melo Neto (1985) [1]

In the early 1980’s, Brazilian psychoanalyst and thinker Fabio Herrmann (1944-2006) defined what he described as a regime of attack, a state of affairs that explained then recent events, particularly the attempted assassination of Pope John Paul II, but also John Lennon’s assassination and Ronald Reagan’s attempted assassination.

Herrmann’s ideas developed at that time about thought and action seem useful to think about the world we now live in, especially in this prescient moment when a string of mass shootings harrows American society, as well as other societies around the world. It is not a particularly new trend, of course, but has seemed disturbingly frequent as of late.

Herrmann’s text is extremely complex and sophisticated rendering it impossible to summarize. We strongly encourage the reader, especially any readers that understand Portuguese, to seek out the original text. Here, we will parse a few ideas for an initial discussion, presenting some fragments that may help think about this phenomenon.

A question remains

When Pope John Paul II was shot at St. Peter’s Square in 1981, he wondered: “Why me? Why the pope?” Based on this simple, spontaneous reaction, Herrmann makes various interesting considerations. “It expresses the incredulous surprise of someone who is shot (Why me?) and also a reflexive principle (why the pope?)” There is the beginning of a shift: from target of an attempted assassination to a person (me?), and from person to the subject of a reflection (why?) In a way, it was the man who became the pope, Karol Józef Wojtyła, who wondered: what have I become that is now the target of assassin intentions?

It was the very victim of the attempted assassination who initiated an analytic process: the first person to return thinking to an action. What we can now do is take this a little further.

The world we live in

My understanding of Herrmann is that, for him, we do not think about the world we live in: it is the world we live in that thinks us. Information, or “opinions,” are conveyed to us in newspapers and heated debates, and they become truths, in the sense that they dictate our world and are defended forcefully. Rather than pondered arguments, these truths are akin to “positions” in war. There is zero or minimal critical thought, and those holding such positions seldom accept counterarguments or a productive discussion.

As a result, our contemporary world is one where a lot of people feel great impotence, and they measure their worth against that of great personalities, or at least that was the case in the 1980s: how was Lennon able to get so big when my own life is so small and insignificant?

Lacan and Herrmann

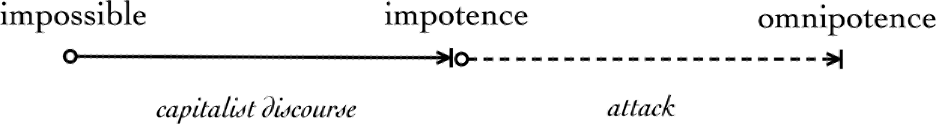

The capitalist discourse was defined by Lacan (Seminar XVIII) as a transformation of the impossible into impotence. Not that it is impossible to reach an ideal, but that you failed. Such a discourse disguises structural impossibility as individual impotence, a conversion that is synthesized in the word: loser.

By contrast, Herrmann defined attempted assassination as a transformation of impotence into omnipotence. “The impotence revealed by an attempt is masked as omnipotence.” Through an isolated and destructive act, an individual is trying to alter the order of the world.

These two formulations can complement each other:

The capitalist discourse is sustained by a celebrity. A repetitive celebration that constantly throws the unattainability of an ideal in you in the face. You-loser failed. The one who operates the abrupt inversion of the state of impotence is the author of the attempt. The characters whose destiny (reciprocal unconscious) is to meet: “The attempt is the [wordless] dialogue between the last two individuals of modernity,” Herrmann writes — a “hello in the form of a shot.”

On one end, we have a celebrity whose function it is to sustain the capitalist’s discourse, to throw in your face that the ideal is attainable: you-loser failed. On the other end, we have the author of an attempt who operates an abrupt and suicidal ending for the state of impotence. Both are like characters whose destiny (reciprocal unconscious) is to meet: The attempt is the [wordless] dialogue between the last two individuals of modernity,” Herrmann writes — a “hello in the form of a shot.”

Social media

With social media, this seemed to change: individuals, at first, felt empowered and that their voices were finally heard, as they shared their “positions” on platforms such as Facebook or Instagram. They felt as though their opinions were equivalent to those of famous journalists, that they had readers and “followers.”

Over time, it has become clear that anyone can post anything online, flood the internet in that way, but their influence is still restricted. Having or lacking followers became a great source of preoccupation and frustration for many in our society. They remained impotent, now not only individually but as large pockets of people.

Pure acts

Those who attempted to take the lives of the Pope, Lennon, and Reagan were unable to tolerate their own insignificance, compared to these great personalities, and they performed acts of rage. Actions, Herrmann explains, are merely coagulated thoughts; they are opinions taken to the last consequences. Ultimately, they are pure acts.

Pure acts “declare their reasons” and therefore “cannot be explained,” says Herrmann. They are self-destructive gestures, in the sense that the perpetrator either dies or is sentenced to life in prison. But the need, the internal drive to execute the act, the killing spree, is so great that nothing else matters, not even the life of the killer. Pure acts are not rational—or, if that is impossible, they are only very minimally rational—and they are highly symbolic.

Back to the present

How do these ideas help us to think about what is happening in the United States today? How may we recontextualize Herrmann’s ideas from the early 1980s to 2022. What we see today in the United States are mass shootings, not single assassinations or attempted assassinations of highly charismatic personalities. Very often, they are live-streamed on social media, which was unimaginable in the 1980s. And some of the targets have been children as young as five years old.

But the impotence of the killers today seems the same. The need to act. Also, Herrmann had observed that assassins were mainly male, and this also remains true. Despite how frequent mass shootings have become, I do not remember any female mass shooters.

What Herrmann described as psychosis of action seems to prevail. That is, the shooter does not think, he is thought by the world he lives in, and the thoughts that think him are deadly and poisonous. He performs pure acts, as is characteristic to psychosis of action, a tragic form of collective psychopathology.

It is possible to think of American mass shooters, usually male, and often aged between 18 and 22 years old, as suffering from impotence, in the sense of feeling unable to make a difference in the world, of feeling insignificant, and this form of psychosis as psychosis of action.

If this extremely brief diagnostic picture is at all accurate or relevant, the next question becomes: how do we reintroduce critical thinking in our world? This itself seems critical. These thoughts that are thinking us, or so many of us, involving guns and shooting up facilities need to be scrutinized and shaken.

[1] Translation by Dylan Blau Edelstein and Fernanda Sofio. Original Portuguese from “Sujam o suicídio” In Poesia completa e prosa. A.C. Secchin (Org.), Rio de Janeiro, Nova Aguilar, 2008. p. 549.

Authors

Leda Herrmann

Leda Herrmann

Full Member, Training and Supervising Analyst at the Brazilian Society of Psychoanalysis of São Paulo; Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology (Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo); author of

Andaimes do Real: A Construção de um Pensamento [Scaffolds of the Real: The Construction of a Psychoanalytic Thought], among other texts.

Luiz Moreno Guimarães Reino

Luiz Moreno Guimarães Reino

Affiliate Member at the Brazilian Society of Psychoanalysis of São Paulo; Ph.D. in Social Psychology (University of São Paulo); author of the dissertation

Destino e Daimon na Psicanálise [Destiny and Daimon in Psychoanalysis], among other texts.

Fernanda Sofio

Fernanda Sofio

Active Member at the American Psychoanalytic Association; Ph.D. in Social Psychology (University of São Paulo), author of

Literacura: Psicanálise Como Forma Literária [Literacure: Psychoanalysis as Literary Form], among other texts.

Return to

Everyday Psychoanalysis Blog