Img:

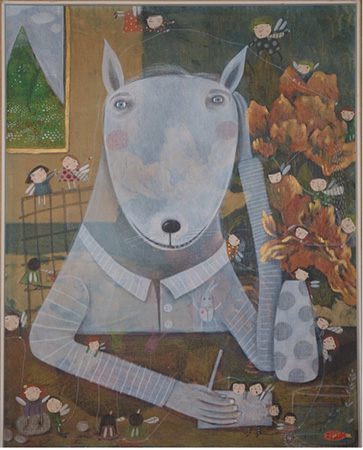

Anime/Souls (Manufatti, 2017)

COCAP Blog: Franco D’Alberton writes on Psychoanalytic Interventions with Children in Hospital

In this blog, basing on my experience as a psychoanalyst working in a paediatric ward of a university hospital (D'Alberton, 2022), I want to focus on the importance of groups as a modality for ameliorating health and decreasing emotional stress and suffering of children, parents and healthcare staff.

Psychoanalysis, in fact, can contribute to the culture and clinical practice of a healthcare institution by paying attention to the emotional experiences of individuals and groups, using tools that allow the emotional vicissitudes of both patients and professionals working with them to be shared and worked through.

Group treatment has proved effective in various areas of clinical practice and particularly productive in those situations in which it is difficult to give symbolic and communicative expression to the contents that inhabit the deepest levels of emotional life.

Our work with groups is based on the Bionian theoretical model (1961), according to which the group mental apparatus allows the transformation of unthinkable anxieties, through which modulation and possibilities of expression are obtained. Our experiences have confirmed the significant degree to which the group experience carries within itself the effect of a multiplier flywheel for the elaboration and transformation of psychic experiences that in other conditions would take much longer.

The setting of the meetings I refer to involves sessions of one hour and 30 minutes, on a weekly basis for children and adolescents, every three to four weeks for parents and staff members: they are led by a psychologist-psychoanalyst and, when necessary, a medical specialist, as well as an observer, usually a psychologist in training. Meetings do not have a specific theme or agenda; participants have the opportunity to talk about any aspect of their experience that they wish to bring to the group's attention.

Basically, at the first meeting, the leader introduces himself and the group and talks about the timing and frequency of the meetings and the fact that each member can talk about anything crossing their mind; with children it is added that they can talk about anything, but they cannot physically harm themselves or put themselves in a situation of real danger.

Groups with children and adolescents

A group of preadolescent outpatients who had been hospitalised for somatic symptoms of various kinds with a probable emotional origin met weekly, while once every three weeks the parents met with a colleague at the same time. In a room that lent itself to this use, there were several chairs, a box of toys, writing material and an individual folder with paper and crayons - basic material for each child. The children present soon grew to six, an initial nucleus that adapted over time as new participants arrived.

At the first meeting, after the conductor introduced himself and talked about the timing, the frequency of the meetings and the minimum rules, the participants introduced themselves by telling their names and the reasons why they had come into contact with the hospital; some of them pretending to attend an Alcoholics Anonymous session, like they had seen in some movies.

In this first session, a ball tied to a rope that was thrown here and there seemed to allow the boys to be already immersed in topics that would be addressed over the three years of the group's duration: detaching from the parents of their childhood, particularly one's mother, while at the same time maintaining a connection.

The boys seemed to go to great lengths to establish connections, announcing early on that the issue was one of letting go but at the same time being held.

As the weekly meetings progressed, the group agreed to experience something they had not been able to experience by getting in touch with their feelings. Especially since it is not easy for pre-adolescents to put into words what they feel, the group was a meaningful learning experience for them, a place where they could learn to express themselves and perhaps think about something that had not previously reached that form of expression.

Groups with staff members

In addition to group interventions dedicated to patients and parents of hospitalised children, groups dedicated to hospital staff demonstrate a particular impact when they manage to connect with the resonances that professional life arouses in the subjectivity of health workers (Menzies, 1960).

The material that follows derives from a series of meetings of a group formed by the staff of two cohorts of doctors and nurses who, following a merger and reorganisation, were unified into a single operational unit.

In one session when the group's activities were consolidated, a nurse began to recount that the previous day she had greeted the parents of a child who was unwell and, on meeting them outside the hospital shortly before the start of the group, had learned that he had died. The group shared the nurse's emotion and wondered if one could ever get used to children dying, a rare enough event in that ward.

The group allowed the participants to talk together for the first time about the deaths of the little ones that have dotted the life of the hospital ward over the years. 'Bodies in the closet', for whom the grieving process - which they had all kept inside without being able to share - thus found a way of being addressed. One participant said: 'I am struck by the intensity of the feelings that emerged in a situation where I would normally tend to slam the door at my back.

There had been an opportunity to talk about the anger at the way the death of some children was experienced and the tenderness that surrounded the death of others. It is not true that one grieves more for the loss of children towards whom one feels more affection. The deaths of X and Y, two children who disappeared in recent years, were compared. While X behaved well in the period leading up to his death - and this was a source of comfort and consolation for his parents and staff, who had the opportunity to say goodbye and attend the funeral - Y never stopped suffering and, according to some, was not helped to suffer less; he did not have the opportunity to experience a 'good death'.

Relieving these events of mourning also reminded the participants of the deaths in their personal histories, put them in a state of emotional revisiting of these events, and in the group, there was continued discussion of good and bad deaths. Good deaths were those in which the connections had not been truncated and the work of mourning had been completed. The identification mechanisms had allowed aspects and characteristics of those who had left to find a place within their loved ones. About one of these children, one person said: "I remember him with tenderness. Sometimes I still see his mother and we greet each other with affection".

The bad deaths were those when the persecuting monsters came to cover those who were left behind with guilt, when grief and anguish broke the bonds with the child, and when, even because of therapeutic obstinacy, there was a feeling of not having done everything possible to help the child come out peacefully, or when for, it was not possible to say goodbye.

Participation in group activities was not unanimous. Not everyone who started attending meetings continued to attend them. Perhaps an experience so unrelated to logic and hierarchical reasoning exposed them to too many anxieties of disorientation or depersonalisation. A coherent and stable core was formed that formed the backbone of the experience and the group's work, like a pebble of meaning thrown into a sea of non-thought, turned into waves of resonance and empathic sharing that could reach even distant institutional places.

Bibliography:

Bion W.R. (1961) Experience in Groups and other papers. Tavistock Publications, London.

D’Alberton F. (2022) Psychoanalytic Work with Children in Hospital. Routledge, London, New York.

Menzies Lith, I. (1960) A Case-Study in the Functioning of Social Systems as a Defence against Anxiety: A Report on a Study of the Nursing Service of a General Hospital. Human Relations, 13(2), 95-121.

https://doi.org/10.1177/001872676001300201.

Author:

Franco D’Alberton is a child and adolescent psychoanalyst and a training analyst of the Italian Psychoanalytic Society and the International Psychoanalytical Association.

Back to Children's Minds in the Line of Fire Blog

Back to Children's Minds in the Line of Fire Blog