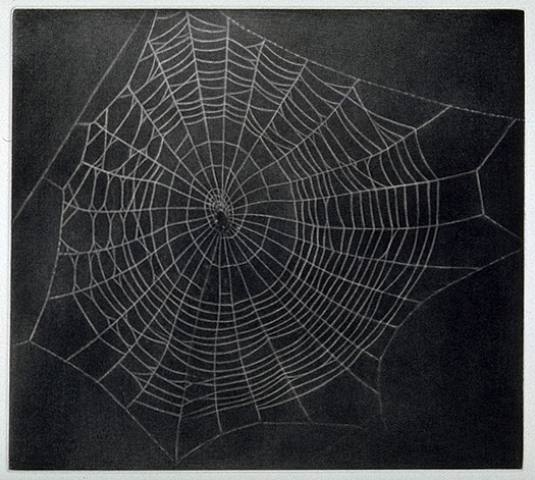

Untitled (Spider Web). Vija Celmins (2000)

Children's Minds in the Line of Fire Blog (COCAP)

Weaving and Unweaving Webs of Gender

In the past several years, many children and adolescents in my San Francisco based practice are exploring a range of gendered possibilities. Children in some of the Bay Area’s more progressive schools are being taught that gender is not conflated with anatomy and is socially constructed. They are introduced to a variety of possible gendered expressions and encouraged to think about them.

On the whole, with children and adolescents in my practice, as the range of gendered possibilities has opened, the turbulence that has accompanied this exploration has been generative. Unsurprisingly, for these patients, gendered embodiment reverberates with desires, anxieties, conflicts and fantasies. These patients also often express a palpable sense that gender is not given or essential but rather open to transformation, at least to some extent. I will offer vignettes from my practice and will highlight two themes. First, I will explore the way gender exploration can focus and expose ontological anxieties, allowing them to come more into view. Second, I will give some examples of the kind of psychic work that gender is enabling.

Ontological anxieties

Gender experimentation can focus and reveal ontological anxieties, anxieties related to the nature of being. These anxieties are existential and not inherently pathological, although they may intersect with psychopathology. From an ontological perspective, there is a human tendency to live as if identity were more reliable and coherent than it is. For some children and adolescents, gender exploration reveals how identity constructs are elusive, enigmatic and full of holes. While often incredibly unsettling, coming to bear these anxieties can lead to an increased sense of internal freedom and aliveness.

As one late adolescent patient put it, “Gender is slippery. Period. What even is it? And it’s very real. It’s weird how those things go together.” This patient was three years into his analysis before gender became a focus. He struggled to live up to his father’s expectations that he be more athletic and popular than he is. He had previously questioned his sexuality and had had some sexual experiences with adolescent boys and girls. He felt he was “mostly heterosexual” but felt trapped. He said in his second year of analysis, “I’m looking at all these pretty girls. I’m cramped inside. There’s no room to actually want them because I’m supposed to have them. For status.” It became clear that he was strangled by an introject that was an amalgam of his father, other important caregivers, voices from sports teams, TV shows, and the cultural surround. This introject kept him in a narcissistic and melancholic encapsulation. He could not live up to its demands and he could not stop trying. He began to discover that he envied girls and women. Although he often wavered on this, he felt women were allowed more latitude for emotional expression.

He was able to productively explore this in the transference, yet he often fell into despair about how intractable these dynamics were. He was increasingly sensitive to the contours of his entrapment, but I also at times felt hopeless about his pernicious enclosure. When he began to experiment with his gender, there were a number of transformations that evolved. First, he began to experience with a palpable immediacy, the socially constructed nature of gender. He said, “When you’re seen as a boy, you become a boy. When you’re seen as a girl, you become a girl.” He conveyed the way in which gender is a construction, held in place by cultural contexts that make its meanings seem more sturdy and reliable than they are. During this time, he often felt anxious that I would lock him into place, fix him with my response or even with my look. I felt he had run into what Sartre describes as “the look” and was experiencing the way my gaze could collapse his nascent sense of a new possibility. Second, even as he was experiencing an enhanced sense of authenticity and internal flexibility, he also ran into a kind of existential dread. As he began to experience the constructed nature of gender, in his lived experience, he felt unmoored and sometimes anxious that his sense of self could unravel. “When you pull out the fabric, holes open and you could fall through.” While there were certainly dimensions to this anxiety that involved his personal history and internal world, I think he was also becoming increasingly sensitive to an existential reality that belongs to being human.

Psychic work

As some of my patients have begun to viscerally recognize gender’s constructed quality, they have felt less enslaved to its pseudo essence and less victimized by gender tropes. Accompanying this shift, they have begun to own their desires and preferences, both with regards to sexuality and more broadly.

To return to my late adolescent patient, he was unusually eloquent in describing the script that we could not seem to loosen. He said, “Boys on top. Girls on bottom. I don’t like that template. We’re all slotted into categories.” At another point, he described that template as evoking a feeling that he was “begging inside myself… I’m excited but I’m not turned on.” As he went through a period of exploring a non binary identity, he said, “It’s a way of saying something is fluid about me.” He described dancing with an adolescent girl at a party. “I didn’t have to dance. I could move. There was space and I actually wanted her.” I said, “Not just for status.” “Exactly,” he replied. He was beginning to move from a position of narcisstically acquiring another, as his father had related to him, to generatively desiring another. It was surprising to both of us how crucial gender was in this movement.

A thirteen year non binary patient had lost their mother to cancer when they were five. They physically resemble their mother and were told that frequently. About a year into treatment, they said in tears, “Everyone says ‘you look so much like her.’ I’m not her. And when I realized I’m not a woman, it felt like it helped. It helped me feel like I’m not her.” There was certainly grief in their description. I also felt anxiety. I said later, “I get the feeling that you’re worried that I’ll think that you’re not really what you say. That I’ll think, well if this is about your mother it’s not true.” They nodded and sobbed.

This patient only had vague memories of their mother. In most of these their mother was already quite ill. Their mother occupied an idealized position in their mind and in the family. At times their internalized mother felt like a hollow figure that provided little containment. They had a vague and persecutory sense that they were meant to live the life their mother did not, yet they had no real sense of what her life would have been. They had a chronic sense of shame, failure and a difficult to locate rage. Prior to their gender exploration, which they were already involved in when they began treatment, they had been in masochistic relationships with other girls, and were depressed.

They felt conflict about the work their gender was doing for them. They were anxious that they were betraying their mother. They were also anxious about the meaning I would make of their revelation. We talked about the way in which gender is always doing work for people. Their gender was enabling more differentiation. My patient was worried that I would take this as evidence that this was the “real,” read defensive, meaning of their gender.

There were clearly transferential dimensions to their worry about what I would make of this. They had frequently had experiences of important others claiming that they were confused and misguided about their experience. I felt their anxiety was relevant for essentialist trends in psychoanalytic history. Psychoanalysis has at times reinforced cultural norms as givens and have read deviation from those norms as pathology. The current expansion of gendered possibilities offers a generative challenge to lurking essentialist strands in psychoanalytic discourse.

Author

Kristin Fiorella, Psy.D., MFT, is an adult psychoanalyst in private practice in San Francisco, CA. She is a child and adolescent candidate at San Francisco Center for Psychoanalysis and is the IPSO North American representative to the IPA Committee on Child and Adolescent Psychoanalysis.

Back to Children's Minds in the Line of Fire Blog

Back to Children's Minds in the Line of Fire Blog