Barbara Young, M.D.

Biography in Photographs on My 100th Birthday

—October 27, 2020

“The only person I can compare her to is Beethoven. I envy her ability to turn anguish into beauty.” –Howard Spiro, Yale University Department of Humanities in Medicine. 1977.

When I was four, I loved to crawl through the large crates in the basement that my father had made in order to transport two heavy wooden chairs from New York to the Midwest, where we lived.

But that was before I was born! It was hard for me to conceive that life had existed without me! — I paused in my crawling — Then my mind turned upward — I had learned that a little boy had died in the bedroom of the parsonage above. Everyone dies. I was going to die!

It was hard for me to believe that life would go on without me!

But then I had a reassuring picture. A firm gold chain ran from the world that existed before I was born to the world that would exist after I died; and I was a link in the chain —

and a very special link in the chain!

That feeling of being special didn’t last long, because when we moved from the little town of Brimfield to the city of Galesburg, the elite girls in fourth grade persuaded me to steal a pencil and — wanting them to accept me — I stole Margaret’s pencil,

but by so doing I was no longer special in my own eyes.

In June 1951, I started my private practice in a small apartment in The Latrobe, in downtown Baltimore. I enjoyed my work with patients, but the days were long and I was lonely and feeling increasingly depressed. With encouragement from my doctor, in 1957 I made my first trip to Europe, to attend the International Psychoanalytic Meetings in Paris, and remained for over a month, visiting friends and enjoying two weeks of relaxation at a resort on the Mediterranean Sea. Sitting on a mossy rock, I dreaded the reality of going home —

I have been so happy here. Isn’t there some way I can feel this way at home?

By the time the ship docked in New York, I had written two stories. I had decided to go to the Bahamas for several weeks in February and, at least for a time, to take two months away from work in the summer. One of my patients — an artist herself — told me much later, “Of course I was angry when you were gone so long; but where would I be if you hadn’t?”

These two stories served as the jumping-off point for my inherited gift to create. Soon photographs began to appear with my words. At that time, color photography was not yet considered an Art. The Metropolitan Museum of Art had a contest and my photograph

Loch Lomond 1960 was accepted. I took it to Herman Maril, a well-known artist in Baltimore, to see what he thought. He covered the stony shore on the right side of the picture, and said: “Now you have an abstraction.” (Several copies of

Loch Lomond 1960 became part of the Baltimore Museum collection, including an expensive dye-transfer print.)

Herman Maril had confirmed that what I was doing was Art. I didn’t holler to my friends, “Hooray!” I quietly kept it to myself.

“I have a secret. I am going somewhere!”

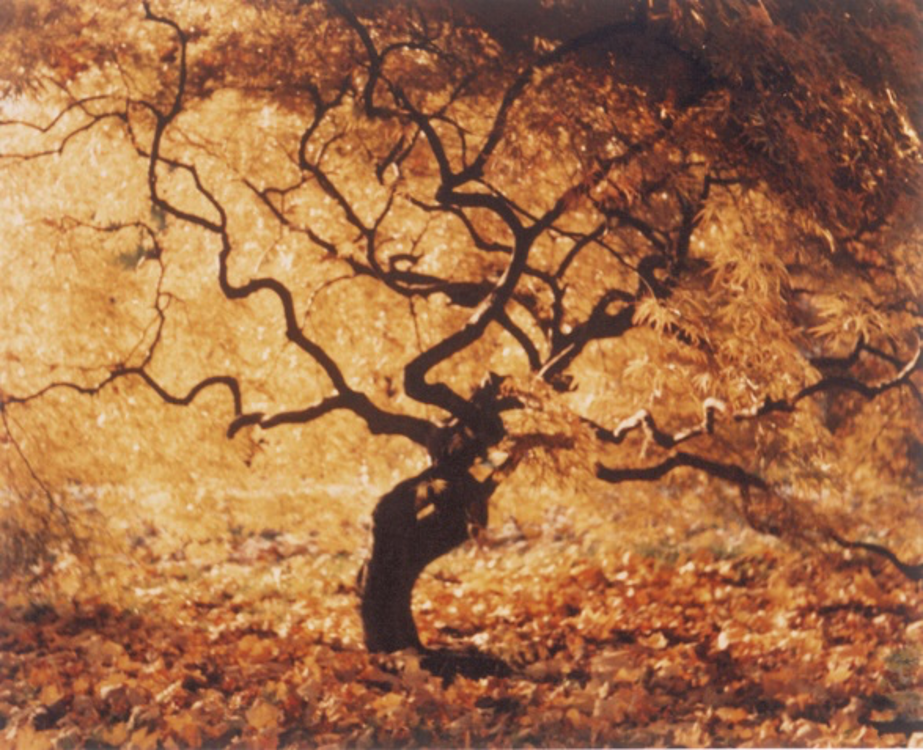

Several years later, Edward Steichen paid five dollars for my

Golden Leaves 1959 to be in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Knowing that I was a psychiatrist, Steichen wrote me: “

Golden Leaves gives the feeling of what might be behind a troubled mind as expressed in the twisted turbulences in nature.” (To me those twisted branches are almost magical.)

In 1969, Beaumont Newhall at the International Museum of Photography in Rochester paid sixty dollars each for

Golden Leaves 1959 and

Jumbay Seedlings 1963. (These figures indicate how little value was put on color photographs at the time.)

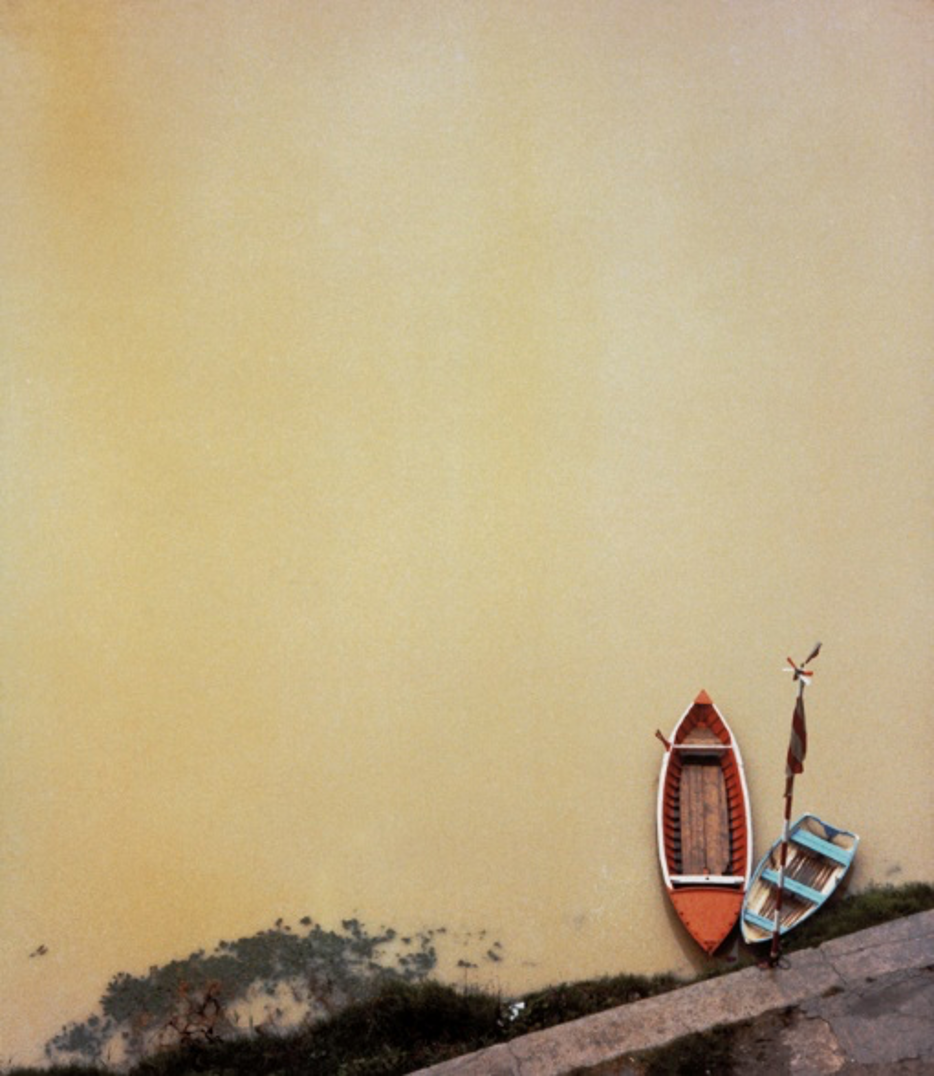

In 1963 I visited the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy. After admiring the famous paintings, I walked out into the hall and took a picture that has turned out to be the most acclaimed photograph I have ever taken.

“

The color photographs by Barbara Young are among the most beautiful in the show.… Uffizi Landing is a stupendous bird’s-eye view of a boat on the water, the shot is a glorious combination of colors and pictorial arrangement.” –David Shirey, in the December 25, 1977, edition of the Long Island Section of the New York Times, commenting on an exhibition at the Port Washington Library.

I hung way out the window with my camera in order to capture those two little boats. Had the great paintings I had just been viewing guided my hands to situate the boats at the lower right-hand corner of the picture, leaving all that empty space?

When I got home and saw the picture, the opposite bank of the Arno River was still in it. With the Masters guiding my hands, I cut out the bank. The picture moved from lying flat to standing up! When Ned Rifkin from the Baltimore Museum came to see my work, he said: “You may not have known what you were doing, but you were making modern art. You have flattened the picture plane.”

Hear that! Modern Art! I took photographs for seventy-one years, from 1958 to 2019. This is the only photograph that — having submitted to this degree of manipulation — has been able to profit from it.

Years ago, a woman who saw a reproduction of

Uffizi Landing fastened it to her refrigerator: “If she is sensitive enough to take that picture, perhaps she could be sensitive to me!” After I had given an illustrated talk on the creative way of life at the Lucy Daniels Foundation in Cary, North Carolina, I received a letter from a young photographer who was in analysis. She realized that she wanted to be that little blue boat docked safely in all that water. She wanted to feel safely moored to someone else. “I didn’t know if the larger boat felt like a parent or a partner — just wanting to be connected in my gut somewhere. It is like a clear knowing; the picture is proof that I will make it to a safe place; quite the best feeling I’ve had in a long time.” Now, in the spring of 2020, a huge print — three and one-half by four feet — of

Uffizi Landing hangs on the wall in front of my lift chair.

The Blue Room 1971.

The Blue Room 1971. This is my best-known photograph. My friend and neighbor Dr. Hugh Davis was converting three row houses near Hopkins Hospital into a birth-control clinic. He called me: “

Cancel your morning patients. I’ve got a picture for you. It will be gone by tomorrow. My wife will pick you up.”

I balanced my tripod on the rickety floor so the row of rooms could all be in focus. Out of the sliver of a window at the end of the row can be seen the Hopkins Medical School two blocks away.

In 1979, I entered

The Blue Room in a contest exclusively for women artists that the National Artists’ Alliance sponsored at the New York University Galleries.

The Blue Room won first prize. I think it was five hundred dollars.

Self-Portrait 1969. Two years before

The Blue Room, Dr. Davis had asked me to take a picture of a woman in perplexity about what birth control method to use. His wife — who had been a model in Denmark — was our model. I called my photographer brother Arthur for the complicated instructions. On a tripod was a forty-watt bulb burning all the time. I must have had the camera on a tripod, too, with the lens open. Behind the model, my visiting father held a flash gun that he set off behind each profile as she moved her head “in perplexity.” When I had a few shots left, I became the model.

Little boys particularly like this picture. Why? They don’t even know me! Are they curious about how I made it? The eight-year-old son of a caregiver at Symphony Manor — a poet herself — carries my book around, opened to

Self-Portrait 1969.

When I entered assisted living in Symphony Manor at Thanksgiving 2017, I left my camera behind. Yet I kept seeing pictures; I needed the help of friends. My aim was to take pictures which represent the many activities available to residents. Now, when I see a finely structured scene I call for my friend and caregiver Karissa. She pulls her mobile from her purse and asks me how I want to frame the picture. Oh, how different life is today! I used to wait weeks even to see the negatives of what I had taken! Karissa can show me the picture right away. Then she e-mails it to David Orbock, who crops it precisely, digitizes it, and prints the images any size I want.

Gateway to Heaven 2019

Gateway to Heaven 2019. The yoga session is over. Elaine sits relaxing. I notice the symmetry, the columns serving as a gate to the foreshortened corridor running all the way back to the white window in the craft room. Elaine, in yoga position, wears a white shirt. I ask Paul to sit in the chair to balance Elaine and to make a triangle with the window. When the picture is matted and framed, it is the golden glow of the walls and the magnificent red rug that draw my attention.

If that is Heaven, I’m on the way.

Barbara Young, M.D., Baltimore, Maryland, U.S.A.

[email protected]

"After reading Dr. Barbara Young's biography in photos I want to congratulate her not only for her 100th birthday but also for being able to combine art and psychoanalysis together in an admirable way. There is no doubt that, as she says in her text, she is a "very special key in the chain" of sensitive psychoanalysts who feel, as I do, that in our practice we are very close to art."

Virginia Ungar

IPA President