|

|

|

|

|

|

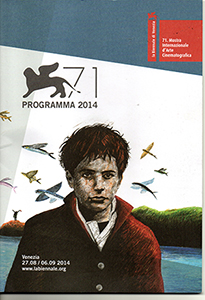

71st Venice International Film Festival,

Venice Lido, Italy

28 August - 6 September 2014

By Rossella Valdrè and Elisabetta Marchiori , Italian Psychoanalytic Society

English translation by: Flora Capostagno

Read in Italian

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"Art is subversive because it is connected to the unconscious.

The more a film is connected to the unconscious, the more subversive it is. As dreams are".

(David Cronenberg)

For the second year running, psychoanalysts from the Italian Psychoanalytic Society (Rossella Valdrè, Elisabetta Marchiori and Massimo De Mari), who share a passion for cinema and psychoanalysis, attended the 71st edition of the Venice International Film Festival, a cultural event of worldwide resonance, sending a daily “live” commentary on the films seen - with their impressions and sensations of the general atmosphere – to the website of our Society (

www.spiweb.it ).

We should remember that cinema and psychoanalysis seem to share an inseparable fate: they were born together at the end of the last century. Since then the magic of cinema, its capacity to portray the dream and the interior world of the humans, have been the subject of particular interest for psychoanalysis. One feeds the other: we agree with Cronenberg in claiming that cinema, as psychoanalysis, is by nature a “subversive act”. Unbound by common sense, it is related to the dream: it has to represent reality, but also to transfigure it, to make it special and poetic through the personal narrative of the director, the specific face of the actor. I may add that having been to other cinema festivals, which have always been excellent, this magic atmosphere is highlighted by the uniqueness of the Venice Lido, an island suspended in the lagoon. A position “in limbo ” which seems to allow images an easier access to the unconscious.

Let's move on to this year’s Festival. For the first time the President of the Jury is a musician, Alexandre Desplat, a French soundtrack composer of international renown, who concluded his Awards' speech with that most French of expressions: Vive la musique! Vive le cinéma!

As always the calendar is rich and varied, offering a scenario of the cinematic arts from around the world: fifty-five films have been presented, twenty of which in competition, plus fourteen shorts and nineteen restored classic (of which the Prize goes to Una giornata particolare by Ettore Scola, 1978 Oscar for the best director and the best actor). The latter are more than mere homage to the past: a serious contribution to the rescue of masterpieces threatened by oblivion, not unlike the restoration of the removed operated by psychoanalysis.

It is impossible to list all the films reviewed and I will restrict myself to the opening film, the much appreciated Birdman by Alejandro G. Iñárritu, acted by Michael Keaton; among the ten or so Italian films both in and out of competition, Hungry Hearts by Saverio Costanzo, with its actors Alba Rohrwacher and Adam Driver receiving the Coppa Volpi as best actors, the dark family saga of Anime Nere. Then the touching biographical tributes to two illustrious names of Italian literature and poetry, Pasolini by Abel Ferrara and the Giacomo Leopardi of Il giovane favoloso by Mario Martone. A fresco of the entire range of human emotions and thus profoundly close to the psychoanalytical view: Hungry Heart and then one of history with the splendid The look of silence by Joshua Oppenheimer, which exposes the underrated Indonesian genocide and wins the Grand Jury Prize (in the emotional words of Tim Robbins, “a real masterpiece”); the malaise of the contemporary family and our children displaying their alienation (I nostri ragazzi); distinctive sociopolitical realities (from the Italian South in Anime Nere, Belluscone to the several oriental films that received awards); the stories of children and adolescents (Terre battue, Le dernier coup de marteau, Sivas, No one's child, Theeb); the unscrupulous globalised economic universe (99 Hommes), the irreducible nostalgia of the Israeli-Palestinian drama (Villa Touma, an all female interpretation) or solitude (Manglehorn).

Serious and high-quality are the adjectives that distinguish this year's selection of films: all of them, as Alexandre Desplat has pointed out, chosen from works encompassing political and social commitment as well as humanism and poetry.

Humanism and poetry. “Cinema activates the child within us”, as Saverio Costanzo has put it. Perhaps the Golden Lion award to the Swede Roy Andersson, A pigeon sat on a branch reflecting on existence, similarly the Silver Lion to the Russian Končaloski for The postman's white nights reflected the desire to privilege the poetic soul of cinema, its mythical fairytale qualities, as well as to highlight the drama and misery of humankind. Even in the most faithful representation of reality, cinema is never a simple reproduction: it is the poetic figure of the author that transposes reality into art.

I would like to stress the originality of the initiative, Tribeca Film Festival as well, supported by the SPIWEB Editorial Board and coordinated by P. R. Goisis, in charge of the cinema area.

http://www.spiweb.it/index.php?option=com_content&view=categories&id=380&Itemid=449

This is a reporter-style coverage whose psychoanalytical content, is far from armchair pedantries and into the living soul of cinema, taking on wholeheartedly the ephemeral side of the show, the thrill and the fun of the competition, with its arguably regressive aspect (but doesn’t cinema ever have a regressive edge?). Then, after the bustle, the analysis.

With the closing of the Festival, as it happens at the end of an analytical process, every film will make its way, has its own life, partially unforeseeable. Like the patient is “forgotten” by his analyst and let go into the world.

The Golden Lion’s winner of Venice International Film Festival: A pigeon sat on a branch reflecting on existence

Rossella Valdrè

---

“Somehow it seems to fill my head with ideas…

only I don’t exactly know what they are”

(Lewis Carroll)

The winner of the Golden Lion award for the best film in the 71st Venice International Film Festival is A pigeon sat on a branch reflecting on existence, the final part of the trilogy by the Swedish director Roy Andersson "on being a human being", which includes Songs from the second floor (2000) and You, the living (2007). Receiving the award Andersson said: "I am very moved, the reason I became a director is my love of Italian cinema", citing De Sica's Bicycle Thieves. He added: "You Italians have good taste", even if there is the risk that Italians will never see his film at their local cinema, since at present it isn't due for distribution. This is an irony of sorts, in keeping with the desolating sense of frustration which runs through the reflections of the "pigeon".

The film is made up of thirty-nine static shots, a sole imperceptible movement by the camera, commented on by title-cards. Thirty-nine windows into the human condition. Thirty-nine pictures wonderfully framed, from which a livid light emanates which strikes the audience with the sharpness of its profiles, the perfection with which the figures are outlined, the backdrop. Each detail is a necessity, each movement by the characters has a sense, each line delivered contains strata of direct and indirect messages which engage the audience on a conscious and unconscious level. Each scene is simultaneously of crude and cruel reality and, at the same time, it is abstraction and metaphor. Each shot is saturated with humoir noir, which forces laughs from between clenched teeth.

The first scene, which inspires the title, is about a man who stares dazedly at a stuffed pigeon in the display cabinet of a dusty natural history museum, while his wife waits for him, perplexed. Afterwards: a man dies of a heart attack while trying to open a bottle of wine; limping Lotta of Gothenburg sings, to the tune of Glory, Glory, Hallelujah, about grappa served in exchange for kisses; in a bar on the outskirts of some out-of-the-way town, King Charles XII enters on horseback with his soldiers on the way to fight the Russians and wants to take the young waiter to his tent; soldiers from the past force a group of natives inside a large container and proceed to roast them; a flamenco lesson with the teacher molesting a young male student. These and more are the characters who follow one after the other, coming and going, sometimes preceded by title-cards, in the short scenes which are theatrical in nature.

The most emblematic figures, who return and give continuity to these apparently unconnected fragments of the world, are two salesmen of the "entertainment sector". They look scruffy, grey, imperturbable with ashen and inexpressive faces who try to sell to improbable buyers "vampire fangs which extra-long canines; the classic laughing bag; and a new product which we really believe in, a mask of uncle with only one tooth". Another recurring feature is the phrase said over the phone by one or another of the characters: "I'm happy to hear you're doing fine. Yes, I said, I'm happy to hear you're doing fine". The interlocutor is the audience. We are the ones who ask: "Sorry, what did you say?", and hear the reply: "Yes, I said, I'm happy to hear you're doing fine." Around is utter desolation.

In this way Andersson cites German expressionist cabaret, Brecht, Beckett, Valentin, Buñuel, the paintings by Hopper and Bruegel, the photography of Olaf and he recasts them in an original and rigorous cinematographic form.

During the screening I felt like Alice through the looking-glass (Through the looking-glass and what Alice found there, Lewis Carroll, 1872), where everything is familiar and, at the same time, turned upside down and backwards. Afterwards I thought that this association was not so far-fetched. Carroll was a genius of nonsense and this work has been described as "a bible of the absurd", "a saga of the unconscious", with a quantity of extremely attractive symbols, perhaps too attractive, for the psychoanalyst, as in this film. Its greatest merit is to let us into creative play (Winnicott, 1971), in which reality (internal and external) is a joint production of the artist and the audience, as it should happen in the analytical 'set-ting'. A production which never ceases to surprise, as in "the double vision appearance/reality characteristic of irony" (Sacerdoti, 1987), with which the film is impregnated.

Elisabetta Marchiori